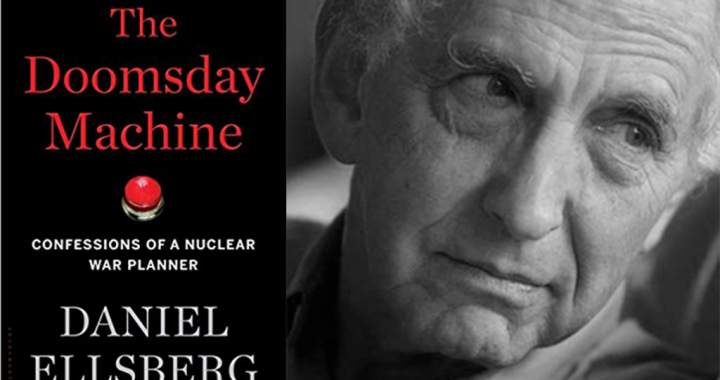

Daniel Ellsberg is known to many for leaking the Pentagon Papers during the Vietnam War. A lesser known fact is that Ellsberg drafted Defense Secretary Robert McNamara’s plans for nuclear war in 1961, and developed an intimate understanding of the madness of the most dangerous (nuclear) arms buildup in history. In his newest book, “The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner,” Ellsberg chronicles the evolution of the “Doomsday Machine” we have created, and offers steps to dismantle it.

Another little known fact about Ellsberg is that he testified in court in support of Ground Zero “White Train” demonstrators on Thursday, June 20, 1985. The next day, on June 21, 1985, a Kitsap County jury acquitted all 19 demonstrators for blocking a train loaded with Trident nuclear warheads on its way to Naval Base Kitsap-Bangor on February 22, 1985. February 22, 1985 was the last time the White Train was used to ship nuclear warheads to Bangor, Washington.

Ellsberg will appear in Seattle to speak about “The Doomsday Machine” at University Temple United Methodist Church on Tuesday, January 9th at 7:30 PM. Tickets are available through Town Hall Seattle.

The following is the full article from the Saturday, June 22, 1985 Seattle Post-Intelligencer, written by John Marshall.

Ellsberg knows the fears of nuclear foes

She cites the writings and example of Daniel Ellsberg, she details her deepening commitment to the non-violent fight against nuclear weapons. Karol Schulkin is on the witness stand in the Kitsap County Courthouse explaining how she came to put her body on the tracks in front of a White Train thought to be carrying warheads for Trident submarines.

It was a tough decision arrived at over years, Schulkin says. Her voice choking, her eyes filling with tears, she explains, “Part of me still doesn’t believe that those trains are still coming and it depends on people like me to try to stop them.”

Many others brush away tears in the packed courtroom this Thursday morning, including Daniel Ellsberg himself. Schulkin’s testimony, he would say later, “went to my heart like a lightning bolt.” People have told him many times that what he has done has changed their lives, but never before has Ellsberg listened to someone say that under oath, someone who is on trial for non-violent actions.

So Ellsberg, an intense and emotional man, fights to keep his feelings under control as Schulkin testifies. For he has been there, too, when the private doubts pile up, depression thwarts action and always there’s the uncertainty that the protest will make any difference at all.

It was that way with the Pentagon Papers, Ellsberg remembers. For two years, he had tried to interest several prominent anti-war senators in the massive Top Secret study of the Vietnam decision-making in hopes of ending the war. But, one after another, they declined. And the war dragged on, the killing continued.

“I didn’t have any confidence the Pentagon Papers would do anything,” Ellsberg recalls. “I still had hopes it might, but it was just a question of feeling the situation was desperate and I had to do what I could. And as Schulkin said, ‘It seemed to be up to me.’ Others could do much more with the papers, much easier, with much less risk, but it was pretty clear they weren’t going to do it.”

The Pentagon Papers would prove to be political dynamite, not only contributing to the end of the war, but to the Nixon administration as well. For Ellsberg’s release of the papers to the press so enraged the administration that it launched a secret “Get Ellsberg” campaign, including the burglary of his psychiatrist’s office. And that set in motion the illegal acts and dirty tricks that became the scandal called Watergate.

After Vietnam, Ellsberg turned his protest efforts toward the nuclear weapons and nuclear war plans that he had once studied and revised as a 30-year-old analyst at the Defense Department in 1961. “I felt at the time that I’ll never do anything as important as this,” he says, “and that hasn’t been eclipsed.”

But Ellsberg’s perspective on the threat that nuclear weapons pose would change so greatly that, 20 years later, he would be arrested in protests at nuclear weapons facilities in Colorado and California. And it would bring him to Kitsap County, where he takes the stand in support of the 19 White Train protesters.

Wearing a gray business suit, his silver hair clipped short, the 54-year-old Ellsberg speaks calmly about why he considered Trident to be the greatest threat ever to world peace. It is, he says, a “first strike” weapon that tips the precarious balance of nuclear terror between the United States and the Soviet Union.

“That’s why we are all now placed in the position of the parents at Jonestown when they were rehearsing suicide with their children,” Ellsberg testifies. “They should have mutinied, they should have told Jim Jones, ‘We will not do that!’”

Later, over lunch, Ellsberg empathizes with the White Train protesters. He talks of the loneliness of protesters who find, as he did, that friends vanish from their lives without a trace. Compensation does come from the sense of community with fellow protesters, he says, and there is some satisfaction, too, in taking action.

But always, Ellsberg says, there’s the constant inner battle with feelings of hopelessness and despair: that nuclear war is just too great a threat and protests against it are just too few and too feeble.

“But God knows,” Ellsberg says, “I don’t think we’ll survive without this.”