Editor’s Note: Although this essay is a tribute to the life of a great prophet, it is even more a call to action. I invite each of you reading this to dedicate or rededicate yourself to Dr. King’s vision articulated in his essay, The World House, in which calls on us to “1) transcend tribe, race, class, nation, and religion to embrace the vision of a World House; 2) eradicate at home and globally the Triple Evils of racism, poverty, and militarism; 3) curb excessive materialism and shift from a “thing”-oriented society to a “people”-oriented society; and 4) resist social injustice and resolve conflicts in the spirit of love embodied in the philosophy and methods of nonviolence.”

****************

As we celebrate the birth of Martin Luther King, Jr., we would do well to contemplate just how far (and yet not so far) we have come since he invited us to build a better world for all people.

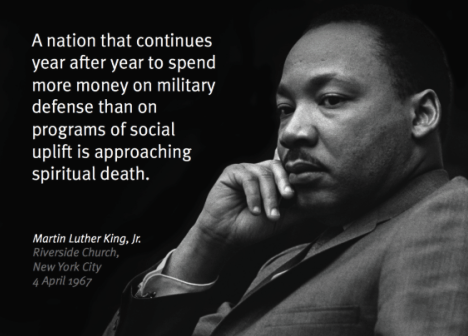

At a time when our nation continues to do damage (and damage control) in places like Afghanistan, supports totalitarian regimes like the Saudis as they destroy another nation (Yemen) and its people, and wonders why so many people in other parts of the world hate us, it is timely to consider the speech delivered by Dr. King over 50 years ago when our nation was immersed in yet another foreign misadventure. Dr. King delivered his “Beyond Vietnam” speech at New York’s Riverside Church on April 4, 1967. It was an extraordinary speech in which he questioned not only the role of the United States in the world, but also the very nature of our economic system.

When we hear about Dr. King – generally once a year around the time of his birthday, January 15th – the news media refers to him as “the slain civil rights leader.” But Dr. King was so much more than that, and our national news media have never come to terms with all that Dr. King stood for. The TV images the media convey are generally those showing him battling segregation in Birmingham in 1963; reciting his dream of racial harmony in Washington in 1963; and marching for voting rights in Selma, Alabama in 1965.

In the early 1960s when Dr. King was challenging legalized racial discrimination in the South, most major media were sympathetic, showing footage of police dogs, bullwhips and cattle prods used against southern African Americans who sought the right to vote or eat at a public lunch counter.

That all changed when, after the passage of the Civil Rights Acts in 1964 and 1965, Dr. King began challenging our nation’s fundamental priorities. He maintained that the civil rights laws meant nothing without human rights, including economic rights. He spoke out against the huge gaps between rich and poor, and called for “radical changes in the structure of our society” to redistribute wealth and power.

By 1967 Dr. King had become one of the country’s most prominent opponents of the Vietnam War as well as a staunch critic of overall United States foreign policy. In his “Beyond Vietnam” speech, Dr. King made a significant leap from fighting for civil rights for African-Americans to morally challenging U.S. dominion over the rest of the world. The “Beyond Vietnam” speech resonates as strongly today on every level as it did a half century ago.

Dr. King spoke of the difficulty of working for peace in an atmosphere of mass conformity. “Even when pressed by the demands of inner truth, men (sic) do not easily assume the task of opposing their government’s policy, especially in time of war. Nor does the human spirit move without great difficulty against all the apathy of conformist thought within one’s own bosom and in the surrounding world. Moreover, when the issues at hand seem as perplexing as they often do in the case of this dreadful conflict, we are always on the verge of being mesmerized by uncertainty. But we must move on.” He went on to say that, “the calling to speak is often a vocation of agony, but we must speak. We must speak with all the humility that is appropriate to our limited vision, but we must speak.” There is no other choice for us, because, “silence is betrayal.”

Dr. King saw the connection between war and the evisceration of social programs in this country. He “knew that America would never invest the necessary funds or energies in rehabilitation of its poor so long as adventures like Vietnam continued to draw men (sic) and skills and money like some demonic, destructive suction tube.” Dr. King saw “war as an enemy of the poor”.

He was amazed that people would ask him why he was speaking against the war. “Could it be that they do not know that the Good News was meant for all men (sic)—for communist and capitalist, for their children and ours, for black and for white, for revolutionary and conservative? Have they forgotten that my ministry is in obedience to the one who loved his enemies so fully he died for them?” He went on to say that as children of the living God, “We are called to speak for the weak, for the voiceless, for the victims of our nation, for those it calls enemy, for no document from human hands can make these humans any less our brothers (sic).”

Dr. King spoke of “a far deeper malady within the American spirit” – greed. He said that it is our “refusing to give up the privileges and the pleasures that come from the immense profits of overseas investments” that governs our foreign policy, and makes the United States the “greatest purveyor of violence in the world today.” He called for a “radical revolution of values” wherein we “shift from a thing-oriented society to a person-oriented society.” He said that playing “the Good Samaritan on life’s roadside…will be only an initial act. One day we must come to see that the whole Jericho Road must be transformed so that men and women will not be constantly beaten and robbed as they make their journey on life’s highway. True compassion is more than flinging a coin to a beggar. It comes to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.”

Dr. King was not afraid to give a dire warning to the American people that, “A nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.” He hammered away at the need for everyone to speak out and use the most creative methods of protest possible, not just against the war, but also for “significant and profound change in American life and policy.” He believed that, “Our only hope today lies in our ability to recapture the revolutionary spirit and go out into a sometimes hostile world declaring eternal hostility to poverty, racism, and militarism.” The sword that we carry is love. “Love is the ultimate force that makes for the saving choice of life and good against the damning choice of death and evil. Therefore the first hope in our inventory must be the hope that love is going to have the last word.”

Just the other day, President Trump referred to African nations, as well as Haiti and El Salvador, as “shitholes,” demonstrating, yet again, not only his own deep, underlying hatred and racism, but also the racism that runs deep within the fractured American experiment.

And worse, Trump has threatened the most extreme violence of all toward North Korea, bringing the world closer to nuclear war than any time since the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. His rhetoric is deeply steeped in violence, and nuclear war is the ultimate expression of all violence, one that would surely bring an end of civilization, and possibly the entire human race.

Dr. King understood the immorality of nuclear war all too well, as Vincent Intondi describes in his book, African Americans Against The Bomb:

When asked in December 1957 about the use of nuclear weapons, King replied: “I definitely feel that the development and use of nuclear weapons should be banned. It cannot be disputed that a full-scale nuclear war would be utterly catastrophic. Hundreds and millions of people would be killed outright by the blast and heat, and by the ionizing radiation produced at the instant of the explosion . . . Even countries not directly hit by bombs would suffer through global fall-outs. All of this leads me to say that the principal objective of all nations must be the total abolition of war. War must be finally eliminated or the whole of mankind will be plunged into the abyss of annihilation.”

If Dr. King was alive today, he would ask why every nation has not yet signed and ratified the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons. He would ask how nations can put selfish, and misguided, self-interest ahead of the interests of humanity. He would ask why nations continue to squander their people’s wealth on militarism and nuclear weapons while ignoring their people’s basic needs. He would ask, “Why, Mr. Trump, is your heart filled with hate?” Of eliminating the threat of nuclear war that looms over humanity he would ask, “If not now, when?”

As he neared the end of his Beyond Vietnam speech Dr. King stated that, “We are confronted with the fierce urgency of now.” Time does not stop for us to sit and ponder our actions. The time is now. “Now let us begin. Let us rededicate ourselves to the long and bitter, but beautiful, struggle for a new world.”

Dr. King’s words continue speak to us today, and with that same great sense of urgency. The odds are great and the struggle is hard. But we have no other choice if we are to build a better world for all. We must act, whatever the cost. To be successful, we need to be in solidarity with each other, in our communities as well as with people throughout the world.

Martin Luther King Jr. left us a beautiful and important legacy of love and nonviolence. He lives on through his words, and beckons us to continue the work of building a just, peaceful world. The best way that we can remember and honor him is to work to build bridges of peace and understanding in our families, communities, and around the world.

And may Love have the final word!

###

End Note: Click here to read the entire Beyond Vietnam speech.