We live in desperate times, with humans increasingly in conflict with each other and our planet. From climate change to nuclear weapons, we continue to push ourselves ever closer to the brink. Never has there been a time when activism was more necessary, and yet neither has there been a time that has demanded so much of activists. We face challenges so daunting that it requires more than sheer will to keep on going and avoid burning out.

How do we, then, keep our activist fires burning. How do we learn to be in solidarity with each other in our common work. How do we grow as individuals, while learning to lead the way, finding a healthy balance of power in our relationships. How do we build a basis for sustaining the long struggle?

These are the challenges addressed in “SPIRITUAL ACTIVISM: LEADERSHIP AS SERVICE,” coauthored  by Alastair McIntosh and Matt Carmichael (published by Green Books, C2016). McIntosh is a Scottish writer and activist on social, environmental and spiritual issues. A pioneer of modern land reform in Scotland, he brought the Isle of Eigg into community ownership. He also negotiated the cancellation of the world’s largest cement company’s plans for a “superquarry” on the Isle of Harris. Carmichael has campaigned on issues including global justice, climate change and fuel poverty since the mid 1990s.

by Alastair McIntosh and Matt Carmichael (published by Green Books, C2016). McIntosh is a Scottish writer and activist on social, environmental and spiritual issues. A pioneer of modern land reform in Scotland, he brought the Isle of Eigg into community ownership. He also negotiated the cancellation of the world’s largest cement company’s plans for a “superquarry” on the Isle of Harris. Carmichael has campaigned on issues including global justice, climate change and fuel poverty since the mid 1990s.

The authors introduce the subject of spiritual activism by stating that “the causes to which any one of us might apply ourselves in life should be more than must mere passions.” As we have so often seen in our activist organizations, many people have shown up all fired up to change the world, and have left not long thereafter, when their brief, yet brilliant, fire burned out. The passion was there, yet something important was missing.

Alastair and Matt go on to say that, “What makes ‘spiritual activism’ so exciting is that it approaches demanding issues in ways that invite an ever-deepening perception of reality and of our positioning – individually and collectively – within it. They understand that “activism entails an openness to life and how it might change us; it is not just about us changing something or someone else. One thing leads to another; we become both transformers and transformed.” Through their life journeys, the authors have come to a deeper understanding of activism as a “process of building community in all three of its dimensions – social, environmental and spiritual.”

In terms of coming to grips with the often difficult concept of spirituality, the book states up front that “religion and spirituality are not necessarily the same thing.” That is an important starting point in which to look at spirituality in the broadest terms in order to welcome all to the table. There is a recognition that religion can either support the development of spirituality or “inhibit or kill it,” and that “most of the great religious teachers have been reformers.” The authors see healthy spirituality as “a way of waking up intellectually to the depth of the problems we face today” so that we may reform the world in our sphere of influence.

As for the question of “leadership,” this book speaks volumes to its complexities and nuances, all with a firm understanding that “a movement is a community”… “a psychological complex.” They speak to the need for “accountability and the legitimate exercise of power,” while remembering that “it takes the whole crew to keep the ship afloat.” Ultimately, its about “servant leadership,” which is “a leadership of doing, seeing and being. It means, quite simply, enquiring constantly where we can be of most service, and usually this requires a willingness to move in and out of roles of greater and lesser prominence.”

Those of us who take on difficult tasks, such as the abolition of nuclear weapons, have, in a very real sense (to quote the authors) “grown in awareness.” To do so, they say, “is to take on a burden.” And therein lies the origin of our journey. Each of us has grown in our awareness, each in a unique way through our individual experience, and have thus taken on this burden. To look away is not an option. To stay the course and not burn out, we must develop a strong, deep, spiritual well in order keep ourselves nourished for the difficult journey. In this way, they conclude, “the burden of awareness becomes a precious burden.”

And, as if the journey has not been difficult enough, it is about to become even more so as a new administration comes to Washington, D.C. We are going to need what Gehan Macleod (in one of the author’s case studies) calls “spiritual bravery.” As she describes “spiritual bravery,” she says that “it means to live each moment by balancing head, heart and hand not by the day-to-day dogma that keeps you ‘in the right’, but by being willing to take the risk with each step that you may be wrong. Being wrong can be a wonderful thing. It’s learning. It’s growth. It is the kind of vulnerability that opens up the space of solidarity. It’s connection.”

Drawing from the Hebrew prophets to Carl Jung, and with case studies that include Sojourner Truth and Julia Butterfly Hill, “SPIRITUAL ACTIVISM” makes a strong case for the “transformative power of spiritual principles in action.” “SPIRITUAL ACTIVISM: LEADERSHIP AS SERVICE” is a book for our times, one that can provide guidance and strength for the journey. May it help us deepen our connection and leadership in humble service to humanity.

Author’s Postscript: I had the honor of spending time with Alastair McIntosh when he visited us at Ground Zero Center in 2016. I asked Alastair to share a brief reflection of his visit; his offering follows.

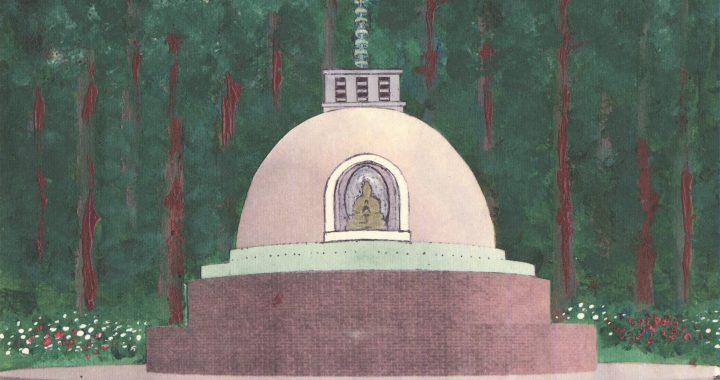

As the guest of University Congregational United Church in February 2016, I was privileged to be taken to the Ground Zero Center that witnesses against Trident submarines at Naval Base Kitsap-Bangor. Coming from Scotland, where I live some 30 miles from the British nuclear submarine base at Faslane on the Atlantic east coast, it was powerful to meet people with the same mission, the same submarines, the same warheads of mass destruction and the same spirit of nonviolent resistance there on the Pacific coast. So many things spoke to my heart at Ground Zero. The ordinary extraordinariness of the people who made their testimony from there. The lack of mainstream leadership structures, and yet, a task orientation that was far from rudderless. And then there was the shrine out in the garden; it contained both a Buddha and Cross that had once been together in the meeting house on the property. One night, two off-duty marines came and burnt down the house, and the Buddha and cross were found together amidst the ashes, having survived the consuming flames. I asked Gilberto Perez, a Buddhist monk who is part of the Ground Zero community, what he made of that. His words etched themselves as charcoal script onto the tablet of my mind. He said: “I truly believe the power of light can come from enduring the burning.”

Click here to purchase the US edition of Spiritual Activism from the Independent Publishers Group.